|

HMCS GRIFFIN / HMCS OTTAWA H31

G - Class Destroyer (RN)

River Class Destroyer (RCN)

Commissioned on 06 Jun 1936 as HMS GRIFFIN, she took part in the evacuation of Namsos, Norway, in May 1940 before transferring in August to Force 'H' at Gibraltar and in Nov 1940 to the 14th Destroyer Flotilla in the Mediterranean. She subsequently took part in the evacuation of Greece and Crete, embarking 720 troops on one trip from Suda Bay. She also escorted a relief convoy to Malta. Transferred to the Eastern Fleet in Feb 1942, she returned to the U.K. in Oct 1942 for major refit at Portsmouth and Southampton, toward the end of which, on 20 Mar 1943, she was commissioned at Southampton as HMCS GRIFFIN. On 10 Apr 1943, despite the objections of her captain, she was renamed HMCS OTTAWA. She joined EG C-5, based at St. John's as a mid-ocean escort, but was removed from this duty in May 1944, to take part in the invasion with EG 11. During post-invasion patrols in the Channel and the Bay of Biscay she took part with KOOTENAY in the destruction of three U-boats. OTTAWA returned to Canada in Oct 1944, for refit at Saint John, N.B.. On 11 Mar 1945, HMCS STRATFORD, returning from Bermuda, was involved in a collision with HMCS OTTAWA in the Halifax approaches, receiving extensive damage to her fo'c's'le. OTTAWA remained in Canadian waters for the duration of the war and was paid off 01 Nov 1945, at Sydney. She was broken up in 1946.

U-Boats Sunk: (1) U-678 (Oblt Guido Hyronimus) a VIIC Type U-Boat, sunk on 06 Jul 1944 by HMCS OTTAWA H31, HMCS KOOTENAY H75 and HMS STATICE in position 50-32 N, 00-23 W. There were no survivors of her crew of 52. (2) U-621 sunk on 18 Aug 1944 by HMCS OTTAWA H31, HMCS KOOTENAY H75 and HMCS CHAUDIERE H99 in position 45-52N, 02-36 W (3) U-984 sunk on 20 Aug 1944 by HMCS OTTAWA H31, HMCS KOOTENAY H75 and HMCS CHAUDIERE H99 in position 42-20 N, 51-39 W

Photos and Documents Ship's Company Photos

Commanding Officers

They shall not be forgotten

Former Crew Members

Photos and Documents

(OTA001) Vengeance Mission Of New Canadian Destroyer // From the collection of J. Vincent Wesley, CPO, RCNVR // Courtesy of Marilynn Taylor (OTA002) HMCS OTTAWA H31 // From the collection of A/ERA 4c, Raoul Bélanger, RCNVR // Courtesy of Pierre Bélanger (OTA003) HMCS OTTAWA H31 - 1943 // From the collection of Rex Duce, Telegraphist, RN // Courtesy of Melanie Brough (OTA004) Child of Canadian sailor on active service transported back to Canada of the child's mother was killed in by V-bomb // Crow's Nest newspaper - Jul 1945 (OTA005) Ontario crew members of HMCS OTTAWA home on leave // Toronto Evening Telegram 18 Oct 1944 // Courtesy of Cal Littlejohn

(OTA006) HMCS OTTAWA H31 // From the collection of Robert Macklem // Courtesy of Bob Macklem (OTA007) HMCS OTTAWA H31 // Photo taken from HMCS OWEN SOUND K340 // From the collection of Dan L. Dunbar, AB, RCNVR // Courtesy of Dan Dunbar (OTA008) HMCS OTTAWA H31 in drydock at the Halifax Shipyards, Spring 1945 // Source: Canadian Virtual Military Museum on Facebook (OTA009) HMCS OTTAWA H31. Photo taken from HMCS MATAPEDIA K112 // The Frisken photo collection (OTA010) HMCS OTTAWA H31 // Courtesy of the Naval Museum of Halifax

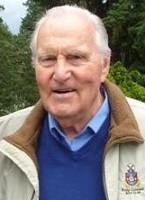

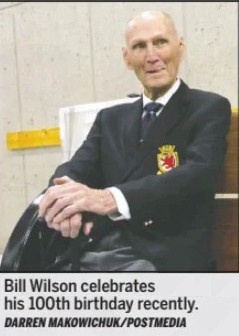

After friend was killed by U-boat, Calgarian joined crew of ship chasing them The Calgary Herald 09 Nov 2024 BY Brian Kaufmann After his best friend perished in a U-boat attack on a Canadian destroyer, Bill Wilson knew he wanted to fight aboard the lost ship's namesake successor. In September 1942, HMCS Ottawa was struck by two torpedoes in the Atlantic Ocean while escorting merchant ships on their way to the U.K. The second torpedo launched by German submarine U-91 broke the stricken vessel in half. Among the 134 sailors who died in the attack was 20-year-old Ordinary Seaman Cliff Rasmussen. “His ship was sunk off Newfoundland, he was my pal, on his first trip,” said Albertan Wilson, who, like Rasmussen had been a Winnipeg sea cadet looking to do his part in the war effort. When the sunken vessel's successor ship was docked in Halifax in March 1944, a 19-year-old Wilson, who'd been pulling shore duty with a rifle slung over his shoulder, said he was asked which ship he'd like to embark on. “Without any hesitation, I said the Ottawa 2. We sailed the next morning,” the still-rangy naval veteran said recently, a day after marking his 100th birthday. Wilson said he wasn't out to avenge the loss of HMCS Ottawa or his friend. “I just wanted to go to sea,” he said. But as it turned out, Wilson would find himself hunting the very same fleet of U-boats that had taken the life of his buddy. By the time he'd joined its crew, HMCS Ottawa 2 had escorted multiple convoys across the Atlantic over the previous year, delivering 540 cargo ships without a loss to German torpedoes. They'd been effective in chasing off U-boats before they could sink the merchant vessels they shepherded. Now his British-built vessel would be part of a five-destroyer submarine-killing team preying on what had been the scourge of Allied shipping but for nearly the past year, had been more often the hunted as the fortunes of war shifted. After training in the north of Scotland, it would ultimately have a hand in destroying three U-boats, the first sunk in an effort to protect the build-up from the D-day landings in June 1944. Wilson

said he'd been initially designated as a gunner but gravitated toward being

a signaller — a crucial role in the success of multiple-ship submarine

hunter-killer teams. Those skills were put to work in coordinating an attack on a suspected U-boat detected off the port of Portsmouth in the shallow English Channel. “We ran over the thing with echo sounders, we weren't sure if it was really a U-boat because there were so many wrecks in the Channel,” said Wilson, whose ship employed depth charges and a hedgehog mortar system that would fire off two dozen bombs in a single stroke. “But we attacked and kept on attacking and oil came up, then papers and clothing but no bodies.” Some of those papers were pages from the log book of U-678's commander, which were kept as souvenirs by the Ottawa 2's crew, said Wilson. Canadian sailors, he said, gained a reputation for learning to use naval technology and tactics quickly. “We really worked as a team (between ships), we were good,” said Wilson. “Once we found a U-boat, it was game over (for them)." With information gained from breaking German operational codes, the Ottawa 2's hunter-killer team could zero in on the submarines, an advantage they used in sinking two more of the U-boats in a span of three days in August 1944, he said. “We also had a good idea from the French underground of how many were coming out from their pens and when,” said Wilson. The hunting team, he said, sank one U-boat in the Bay of Biscay heading to its heavily-reinforced pen in the French port of Lorient — the other while it was leaving its refuge. “We sank those ships with hedgehogs,” said Wilson, of U-621 and U-984, adding there were no survivors from any of the three U-boats destroyed by the team. “One hundred and fifty German sailors are still down there.” But probably the most impressive image among Wilson's wartime memories was the sight of the mighty D-day armada of 7,000 ships and landing craft that delivered 133,000 Allied troops to the Normandy beaches on June 6, 1944. “You could almost walk across the channel on top of the ships, there were lines and lines of them ... it was awe-inspiring,” he said. Wilson would keep his hand in maritime military affairs in the following decades, eventually spearheading the creation of the Naval Museum of Alberta, which would be incorporated into The Military Museums. While he expresses pride in that work, the man who's become an icon in the prairie naval community said he's not optimistic in how Canada's wartime efforts are remembered. “Nobody gives a damn ... people wear poppies now but it's a one-day affair,” said Wilson. “We work to educate about what Canada did in the war effort, but they don't teach that in Canadian history in schools.”

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||