|

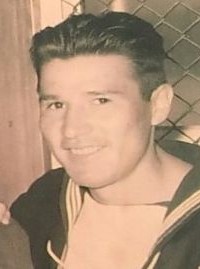

VICTOR FLETT

Petty Officer 1st Class Sonarman, RCN / C.A.F.

(Navy)

From

racism to reconciliation: An Aboriginal veteran's story

Victor

Flett grew up feeling ashamed of his Aboriginal heritage, but buoyed

by a strong family pride in military service. The Sooke widower is

last in a family line of six Aboriginal men over three generations to

serve in the Canadian Forces.

"I

don't remember being proud of being an Indian," said Flett, 89,

who is of Cree descent from the Peguis First Nation in Manitoba and a

decorated veteran with 30 years of service in the navy.

"My

grandmother had First Nations friends and they would speak Cree, but

she wouldn't teach us … We weren't taught our culture because it

wasn't considered something to be proud of at that time.

"But

I did learn about my grandfather giving his life for his country. We

were all aware of that and all very proud of that."

Flett's

maternal grandfather fought and died in the First World War at the

Battle of Vimy Ridge in northern France. His father also served in the

war, but survived.

Flett,

who will give a talk called From Racism to Reconciliation at St. Peter

and St. Paul's Parish Hall on Saturday, visited Vimy last year with

his daughter for the 100th anniversary memorial.

Flett

and his four siblings were raised by their grandmother outside of

Selkirk, about 22 kilometres northeast of Winnipeg. The family decided

to stay in the area after the government moved the Peguis reserve

north in 1907. While the kids of his parents' generation were forced

to attend residential schools, Flett and his siblings stayed in the

one-room schoolhouse in their small town.

"My

grandmother was a Christian and she wanted us to be raised that way.

When she said something, we obeyed," said Flett, who fondly

recalled learning to pray from one of his three older brothers.

His

eldest brother ran away at 14 or 15 and became a marine engineer, then

joined the merchant navy, said Flett, whose three older brothers all

served in the Second World War and survived. One brother landed on the

beaches of Normandy on D-Day with the Regina Rifles regiment.

"He

had some good stories to tell. He said at one point, they were

advancing and went too far. They became prisoners but only for eight

hours," said Flett, looking over family pictures at the church

hall, where he is a celebrated elder.

The

older brother closest to him in age joined the Royal Canadian Air

Force, and they wrote to each other throughout the war.

"He

became an air gunner on a Lancaster bomber," said Flett. "He

saw quite a few fighter planes and shot at them, but couldn't remember

shooting any down."

Flett

said he was not initially keen to join the forces when he came of age.

He wanted to be an RCMP officer and "I was going with my

sweetheart," Flett said about his future wife of 50 years.

When

the dating couple split briefly, he was heartbroken and decided to

sign up for the navy.

"When

she found out, she said our spat wasn't so serious that I had to join

the navy," Flett said. They got back together and got married.

But he shipped out for Korea on the destroyer HMCS Crusader in 1952 as

a sonar man.

"There

were two of us who were First Nations, maybe more who didn't want to

say. The other fellow was from Flin Flon, Manitoba. We were good

buddies," said Flett.

He

said he experienced racist slurs during his service. "But when

you're on a ship, it's close quarters, so I had to not make a big

issue of it to get by."

When

he returned to Victoria, he had difficulties finding work and wondered

if it was because he was Aboriginal. He eventually got a job working

with the Commissionaires to help support his family of five.

It

wasn't until later in life that Flett became more curious about his

Aboriginal heritage. He said he was inspired by the reconciliation

work of the Anglican church. His three children also wanted to know

their culture.

"I

thought I should take it upon myself to learn my culture, and a good

way to do that would be to reach out to First Nations through a church

group," said Flett.

He

joined the Anglican group Aboriginal Neighbours, formed at an Anglican

Synod of the Diocese of British Columbia in the 1980s. The

organization welcomes Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people, with the

goal of building community and cultural bridges, as well as offering

support for reconciliation. Flett said he's been proud to be part of

the group, which has taken part in cultural activities, protests and

mentorships.

He

said he learned from his grandmother to have pride in being Canadian

and find comfort in his faith, "in spite of being ridiculed for

being Indian."

He

would like to see justice and fair treatment for First Nations people.

"We were very unfairly treated in a beautiful country with a lot

of wealth and promise," said Flett, adding: "Not long ago, I

could not see myself doing this, talking about racism and

discrimination. I would be too emotional." (Originally published

in the Victoria Times Colonist 01 Dec 2017 - Published here with

consent of Victor Flett)

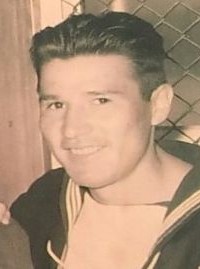

L-R:

AB Ian Henry, Pte Lloyd Adams and Victor Flett

US

Navy Fleet Club, Sasebo Japan - 1953

All

three are First Nations people from Selkirk, Manitoba, Canada

|